The Linear Trap

Most investors live in a linear world. You buy a stock, it goes up 1%, you make 1%. It goes down 1%, you lose 1%. This is “delta one” exposure. It is robust, but it is capital inefficient when you have high conviction in a specific timeframe or magnitude of a move.

Convexity is the escape from linearity. It is the ability to make more money as the move accelerates in your favor, and lose less (at slower rate) as it moves against you. In the language of options theory, convexity is represented by gamma – a second derivative of the option price function.

When you are “long gamma,” your exposure (delta) grows as the price moves in your favor. Paying for gamma is paying for an acceleration of your return profile. But the cost of acceleration is tax called theta – the time decay of your options.

Convexity Toolkit

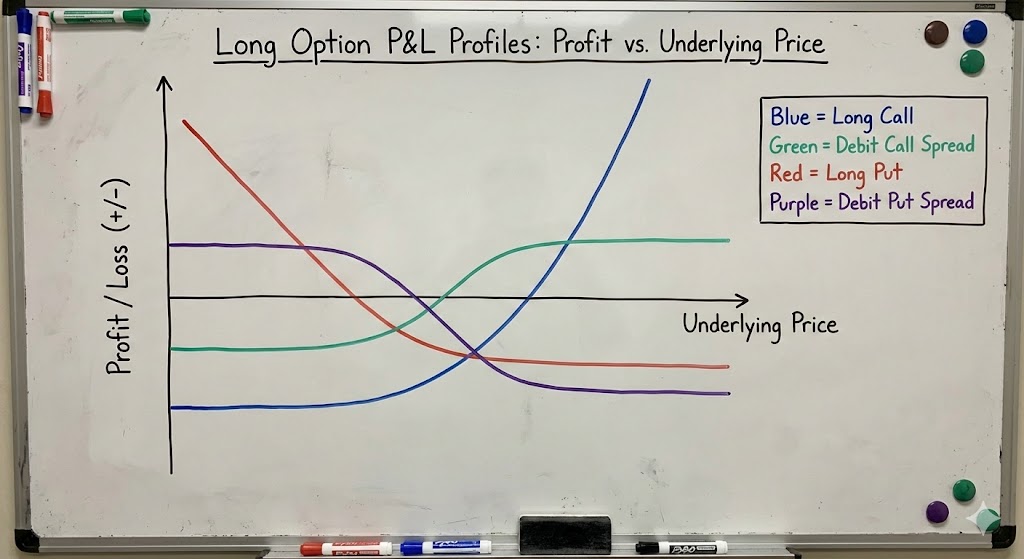

Institutional investors have a plethora of instruments beyond just stocks and options to shape the convexity of their return profiles. The options (pun intended) for retail investors is really just options. There are four main types we will use for layering on convexity to our portfolio return profile – all these are long positions.

- Call – grants you the right to buy a stock at specific price (the strike) before a certain date (the expiry).

- Debit call spread – simultaneously buying a call at a lower strike and selling a call at a higher strike, same expiry. Allows you capture convexity within a “strike window”, but capped upside.

- Put – grants you the right to sell a stock at a strike by a certain expiry.

- Debit put spread – simultaneously buying a put at a higher strike and selling a put at a lower strike, same expiry. Allows you capture convexity within a “strike window”, but capped upside.

Generated using Gemini 3’s “Nano Banana Pro” image generator are the P&L curves of all four option types (looks incredibly photorealistic):

Adding Bullish Convexity

A. The Sledgehammer: Long Call or LEAPS

This is pure upside convexity, with strike (moneyness) being the determining factor for the P&L profile. If deep OTM, this represents a lottery ticket, but as you approach ATM, you gradually approach the “Kelly optimal” risk/reward point for this position.

Deep ITM (delta 0.8-0.9) can also be used as a “synthetic long” position (more capital efficient), while LEAPS (far-dated expiries) can be used as a levered long positions.

You often see professionals layer on call strikes. So if you expect stock XYZ to move violently from $5 to $25 after they past the next critical clinical trial, you might want to construct a laddered call portfolio of strikes at $10, $15, $20 and $25. This allows you to capture increasing amounts of convexity (gamma) in a capital efficient manner.

B. The Scalpel: Long Debit Call Spread

This is my convexity tool of choice. It allows you to very precisely shape the convexity and risk/return you are looking for. The strategy involves buying a call at a lower strike and funding a portion of that cost by selling a call at a higher strike.

The tradeoff with a call: in exchange for getting more leverage in the strike window (strikes between the lower and higher), your upside is capped. So if you think company XYZ will have a significant, explosive re-rating, you would want to use a call instead of a debit call spread to maximize your upside (assuming of course, you have an edge).

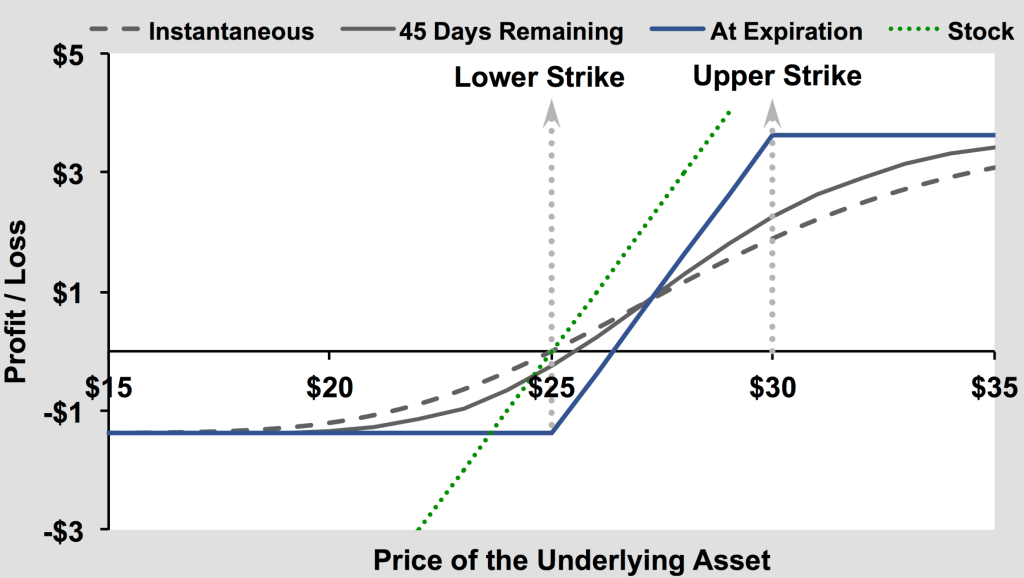

The dynamics of the PnL curve for a debit call spread is actually quite interesting.

At expiration (the solid blue line), you get the expected PnL for a combination of a long and short call at different strikes with the same expiry – it’s just the sum of the individual long and short call PnLs. What is interesting, however, is the evolution of the current PnL curve as the spread approaches expiry.

- Approaching the lower strike:

When the stock is below the lower strike, the spread mimics a naked long call. The short option is too far out-of-the-money to matter, leaving you exposed to negative theta (time decay) while holding positive gamma. You are essentially paying rent on a position that hasn’t started working yet; the PnL curve is depressed below the zero line, requiring a directional move to wake it up.

2. Crossing the lower strike:

As the price breaches the lower strike, you enter the zone of maximum acceleration. This is where the curve is steepest (increasing delta) due to peak gamma from the owned option. However, this is also where time decay hurts the most; the gap between the current PnL curve and the expiration line is widest here, meaning you need velocity to escape the gravitational pull of the strike price before time erodes your gains.

3. Approaching the upper strike:

As the stock rallies toward the short strike, the physics of the trade invert. The short call “wakes up,” introducing short gamma which decelerates your profit accumulation- visually, the curve begins to flatten or “curl” downward. Crucially, theta flips positive; because the short option is now losing value faster than the long option, the passage of time actually lifts your PnL curve up toward the maximum profit ceiling.

4. Passing the upper strike:

Once the stock clears the upper strike, the trade becomes structurally static. The Delta of the long leg (approaching 1.0) is neutralized by the short leg (approaching -1.0), killing your convexity (zero Gamma). You enter a “dead zone” where you are no longer betting on direction, but simply waiting for the remaining extrinsic value of the short leg to bleed out to realize the full width of the spread.

Adding Bearish Convexity

A. Permanent Insurance or High-Conviction Short: Long Put or LEAPS

This is opposite trade of the long call to capture downside convexity. As the underlying stock crashes, your short delta increases (you get shorter) and volatility (vega) usually explodes, increasing the put premium even more. However, insurance is expensive and this is usually reflected in the “smirk” of the volatility smile.

Another use case is to express a high-conviction short position. If you believe say in a short PLTR position but don’t know the short-term will play out (short-lived irrational exuberance), buying a LEAPS put (far-dated) makes a lot of sense here. You are capturing maximum convexity if the stock collapses (like big narrative correction).

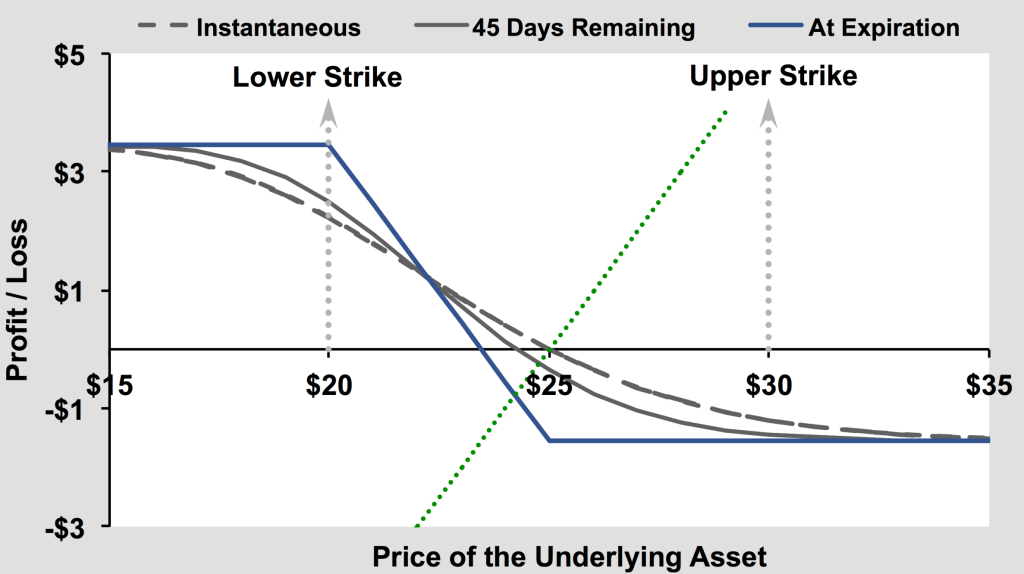

B. Tactical Insurance or Low-Conviction Short: Long Debit Put Spread

This is a favorite tool of mine to express tactical downside convexity, where I want to hedge a macro/economic event that has significant risk (major FOMC or more recently, Trump tariff announcement Apr-25) and I don’t want the drag of permanent insurance (long put). It minimizes the effects of theta (time bleed) while maximizing capital efficiency (less capital to hedge the same exposure).

I also use it to express short-term views – tactical short trades – where I believe a catalyst or event will have material downside risk for a stock within a certain relatively short to medium time frame (3 months to a year), and also minimize theta bleed. A very robust strategy to express downside risk very precisely.

One of the interesting properties about the vertical spreads (debit calls and debit puts) is the PnL behavior starts working in your favor as the underlying price moves through the strike window (lower to upper strike for a debit call, and higher strike to lower strike for a debit put). As this transition occurs, the long position Greeks flip: gamma from positive to negative (deceleration helps), theta from negative to positive (earn carry as time progresses), and Vega from positive to negative (volatility hurts). The Greek inversion is an incredibly beneficial characteristic of vertical spreads that is not present in single calls or puts (long or short).

Case Study: Merger Arb Trade

Let’s say you have identified a potential target Company A that will likely by acquired by Company B. You are going through your merger arb investment process and currently at the execution and hedging step. How would you structure this trade as a PM?

- Pre-announcement: you have done your fundamental analysis and identified the target Company A. Based your analysis, you have determined the range of acquisition prices that make sense for Company B, and from that, arrive at a possible spread for the trade and the expected annualized return range. With high conviction, you may even start adding a position to Company A.

- Post-announcement: your starting position in Company A has significantly increase – you may trim some of the profit based on your analysis of the legal contract of the likelihood of the deal succeeding. If it’s an all cash deal, you maintain or add to your long position. If it involves stock (company A shareholders receive a certain percentage of company B stock), you execute a paired trade going long Company A and short Company B – this results in market-neutral strategy. Adding convexity through the use of debit call spreads may make sense if you have high conviction that the deal will close.

- Post-closing: if liquidity allows, the sooner the better to exit your position especially if you have any options overlay to avoid theta bleed. You are just capturing the spread compression, not any idiosyncratic price movements of either stock, and limited market exposure.

Shaping Skewness and Kurtosis

Here is the paradoxical insight behind why convexity is so important.

A portfolio with a slightly lower expected return (mean) but high positive skew (convexity) allows a PM to size positions larger and use more leverage, often resulting in a higher geometric compounded return over time. You are paying a “tax” (theta) to rig the game in your favor.

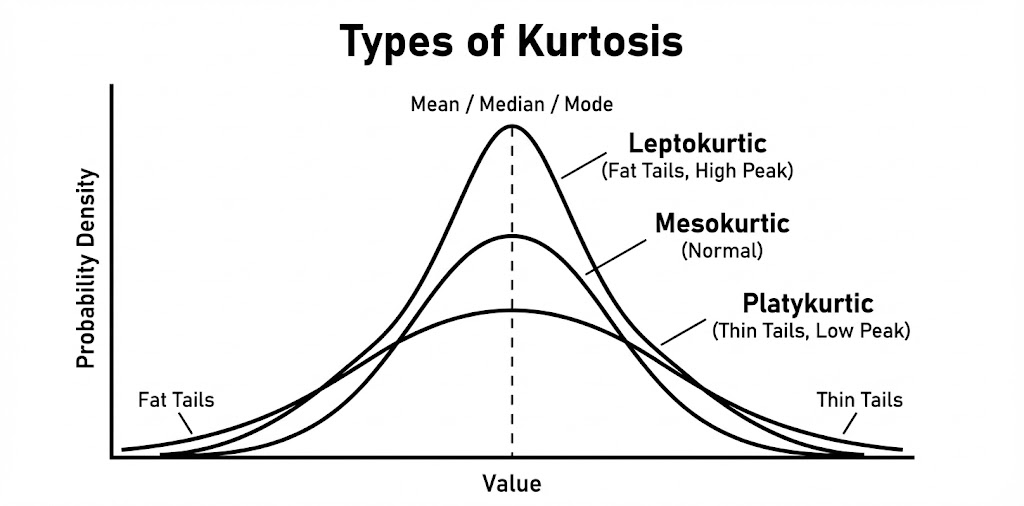

In many ways, a PM’s job is to shape the expected return profile of his portfolio across various moments known as return (first order), volatility (second order), skewness (third order), and kurtosis (fourth order). Options with its convex profile allows a PM to shape both the skewness and kurtosis of their portfolio – something that linear product like a stock cannot.

- Shaping Skewness: with long options, you’re truncating the left side of the return distribution (defined risk) and extending the right side (unlimited upside). You are essentially shifting your portfolio from negative skew (fragile) to positive skew (antifragile), allowing you to profit disproportionately from volatility.

2. Shaping Kurtosis: diversifying linear products (stocks, futures) lead to normal return distributions. However, PMs (especially growth-oriented ones) want fat tails, but only on one side (the chance of a parabolic re-rating). By adding convexity with long options, you are effectively buying “good kurtosis” (outsized upside outliers) while insuring against “bad kurtosis” (outside downside outliers).

Although options get a bad rap due to communities like wallstreetbets who encourage retail investors to bet on short-dated OTM calls and puts – these are not investments, but rather risky gambles (often binary ones too). The true beauty of options is to realize that it adds convexity which can help you shape your return profile, and manage your downside risk in a precise manner.

Leave a comment